Amazon Fires

Why is the Rainforest Burning?

Back before COVID-19 dominated the headlines, before even the massive fires in Australia destroyed thousands of homes and killed billions of animals, another part of the world was burning. I can still remember seeing on an online news article nearly a year ago, in August 2019, the almost apocalyptic images of huge fires devastating the Amazon rainforest. Smoke from the blaze, the article stated, had billowed more than 2,900 km southeast to blacken the sky over the western hemisphere’s biggest city, São Paulo.

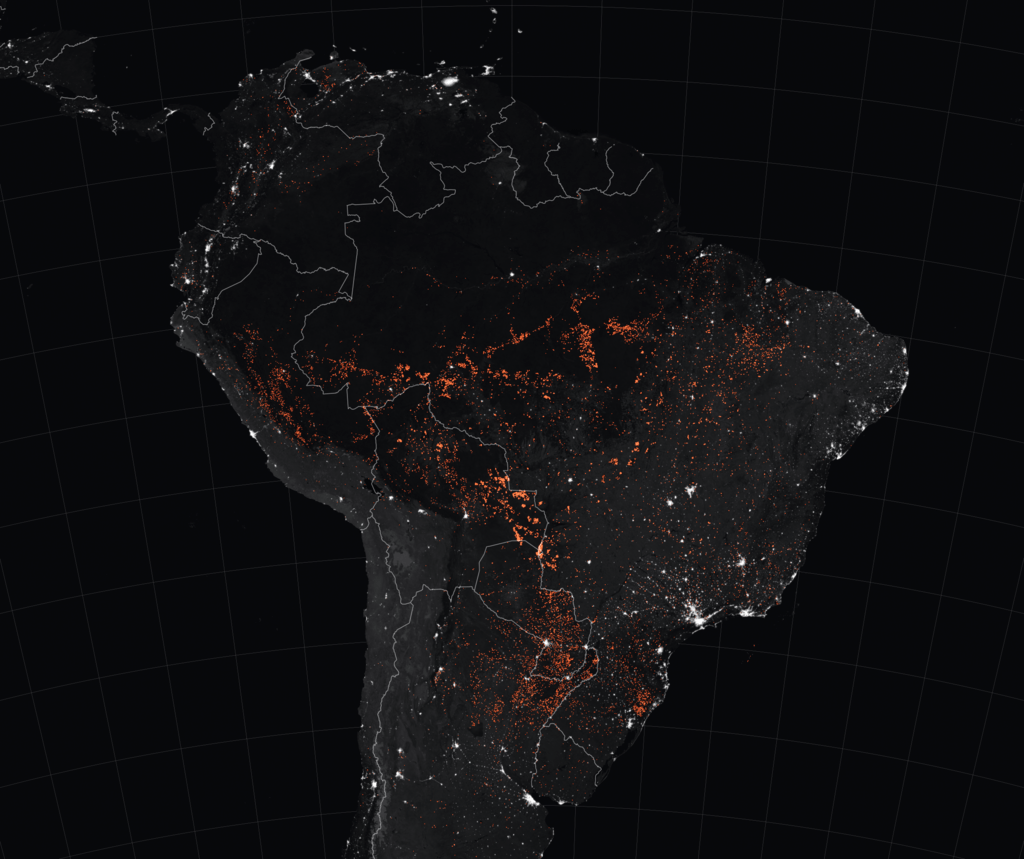

I soon learned that 2019 had been a terrible year for the Amazon. While fires occur there every year, the number and scale seen in 2019 were alarmingly abnormal. There were about 30,000 fire hotspots in the Brazilian Amazon in August alone, almost triple the 10,421 figure recorded in August 2018.

Image Source: Joshua Stevens, using data from NASA

Fires are a natural part of many ecosystems such as the hot, dry savannahs of Africa. But not so the Amazon. Tropical rainforests do not normally burn, and the animals and plants that live in them have no evolutionary adaptations towards fire. It is believed that 99% of all wildfires in the Amazon basin are a result of human actions, either accidentally or on purpose.

So how do these fires start? We all know that deforestation in the Amazon has been occurring for a long time. Forest has been replaced with agriculture, cattle ranching, mining and hydropower generation. Farmers who have already laid claim to the fringes of the Amazon slash and burn the trees and overgraze the cleared patch until the ground is rendered useless, before moving on to clear a new area of forest. Sometimes, the pasture area is not actually used for cattle ranching but is cleared in a ‘land grab’ for later resale using false papers.

Even so, this happens every year. So why was there an 80% increase in the number of Amazon fires in 2019 compared with the previous year?

Exploiting the Amazon

On 1 January 2019, the controversial far-right Brazilian president, Jair Bolsonaro, took office and immediately began showing his contempt for the environment. Upon taking power, he promised to open the Amazon rainforest up to industry. Since then, the man dubbed ‘Tropical Trump’ has consistently weakened environmental protection laws in the country, systematically cut funding for Brazil’s wildlife conservation work, and sacked staff that worked in environmental departments. He has filled his cabinet with people who dismiss climate change as a ‘Marxist hoax’ – a conspiracy designed to keep Brazil from developing as a nation – and who mock assassinated environmentalists (Brazil has one of the highest murder rates of environmental activists in the world).

It is clear that Bolsonaro favours development over conservation. His policies have allowed – in fact, encouraged – ranchers, loggers and miners to destroy the Amazon at an unprecedented pace. At its peak, an area the size of five football pitches was lost every minute. In July 2019, Brazil lost an area of rainforest bigger than Greater London. So while deforestation takes place every year, Bolsonaro and his policies have accelerated it dramatically – and the number of fires deliberately started to clear trees has similarly soared. The Amazon rainforest, it seems, is simply in Bolsonaro’s way.

The increasing rate of Amazon fires was first reported by Brazil’s National Space Research Institute (INPE), whose satellite data indicated a pronounced rise in deforestation. Bolsonaro questioned this data, claiming it had been altered to attack his government. This resulted in a public disagreement between the Brazilian President and the Director-General of the INPE, Ricardo Galvão. For this, Bolsonaro brazenly fired Galvão.

Image Source: Ibama

When the world learned of the travesty happening in the Amazon, President Bolsonaro was rightly criticised by many for his assault on environmental regulations and his cavalier attitude towards this ecological disaster. Some countries, such as France, offered funding to help extinguish the devastating fires. But Bolsonaro, who campaigned for office saying that international alarm about the Amazon threatened Brazil’s sovereignty, declined their help, saying that French President Emmanuel Macron’s offer made him look like a colonial ruler. ‘The Amazon is Brazil’s, not yours,’ Bolsonaro said in response. ‘No [other] country in the world has the moral right to talk about the Amazon.’

Bolsonaro is keen to spread anti-colonialist and anti-globalist messages such as this because it helps him gather support and sympathy from his followers. But this rhetoric is at odds with his plan to open up demarcated territories within the Amazon, which are currently home to hundreds of thousands of indigenous people, for mining, logging and agriculture.

Image Source: David Riaño Cortés on Pexels.com

Cradle of Biodiversity

Bolsonaro is wrong when he says the Amazon ‘is Brazil’s’. Not only because the rainforest extends into eight other South American countries, including Peru, Colombia, Ecuador and Bolivia, but also because the consequences of Bolsonaro’s actions will be felt by the whole world.

It’s almost impossible to overstate just how important the Amazon rainforest is to the health of our planet. Covering an area of approximately 6.7 million km² – twice the size of India – the mighty Amazon represents over half of the world’s remaining rainforests. Its ecosystems harbour 10-15% of the planet’s entire land biodiversity. It is home to a tenth of all known species – that’s approximately 2.5 million species of insect, 40,000 different types of plant, and more than 400 species of mammal. An estimated one in five of all bird species in the world live in this giant rainforest – that’s more than in the whole of North America and Europe combined. One in five of all fish species live in Amazonian rivers and streams. An estimated 390 billion trees, representing 16,000 different species, produce around 9% of the world’s oxygen supply. And, of course, it is home to many species that have yet to be formally discovered – a new species is found in the Amazon, on average, every two days.

Image Source: Corey Spruit

But the Amazon’s biodiversity is just one element of its importance. It also contains 20% of the planet’s flowing freshwater and, perhaps most crucially of all, it acts as a giant carbon sponge, absorbing and storing more than 120 billion tons of carbon that would otherwise be adding to global warming. Chopping down and burning just one hectare (0.01 km²) of rainforest releases the same amount of carbon as circumnavigating the globe in a car 61 times. In total, over 906,000 hectares (9,060 km²) of forest within the Amazon were lost to fires in 2019. You don’t need to be good at maths to realise that this is an enormous amount of carbon being released into the atmosphere.

Recovery of the Rainforest?

In July 2020, the INPE released new data. It showed that the extent of deforestation over the past 12 months was the highest recorded since the organisation started releasing monthly statistics in 2007. According to the satellite data, 64% more land was cleared in April 2020 than in the same month last year – even though 2019 was the biggest year for deforestation in more than a decade. Three days later, almost a full year after the Director-General of the INPE was fired, the top researcher responsible for tracking and analysing this new set of data was removed from her position by the Bolsonaro administration.

It seems that, if anything, the situation is getting worse. Coronavirus certainly hasn’t helped. As of this writing, Brazil has recorded more than 125,000 deaths linked to the virus – the world’s second-highest figure after the USA. And as COVID-19 ravages the country, grabbing everyone’s attention, loggers have accelerated their destruction of the Amazon even further.

Can anything be done? As long as President Bolsonaro remains in power, steering his country towards environmental ruin and undermining the crucial conservation work that would otherwise help protect the Amazon, the situation seems bleak. But there are things we as individuals can do. We can reduce our wood and paper consumption, or look for rainforest-safe products with the help of the Rainforest Alliance. We can also challenge corporations, particularly fast-food giants, to stop sourcing products, such as beef and soya, that are linked to environmental destruction in the Amazon.

And, perhaps most importantly, we can reduce our meat intake. One of the main drivers of deforestation is the world’s surging appetite for red meat. Corporate meat giants are now able to graze cattle in protected areas with relative impunity. By cutting back on the amount of red meat we consume, particularly beef, and by buying more locally-grown food where possible, we can help save the rainforest. Brazil does not need more of its rainforest converted to agriculture. There is already a large amount of abandoned or degraded farmland that can be used, intensifying production in these places if necessary to spare land elsewhere that can be returned to the forest.

Image Source: Quapan

Fortunately, rainforests can, given half a chance, regrow. Indeed, they have done so in the past, for much of what we today regard as ‘pristine rainforest’ is actually secondary recovery from past human occupation. The Amazon basin, for example, was quite densely populated even before Europeans arrived in the Americas. Ancient cities were built on the banks of the Amazon River, clearing vast areas of forest. But over time, as these civilisations were decimated by disease and war, the jungle reclaimed its territory so completely that ecologists have mistaken the regrowth for forest untouched by human hands.

Even so, these are very troubling times. The Amazon not only contains enormous stores of carbon, it also regulates local and regional weather regimes. The rainforest depends on constant rainfall to flourish, but that rainfall itself is sustained by the forests. Take away too many trees and the rain will falter. Once trees die and fall over, they open up the forest canopy, causing the understorey to become drier and more fire-prone, creating a vicious loop. The increased rate of deforestation is pushing the Amazon closer to an ecological tipping point, past which it will be unable to recover. According to the WWF, we are on course to reach this irreversible tipping point by 2030. If that happens, its capacity to absorb carbon will be severely diminished and we will lose that wonderful riot of biodiversity that the world’s largest rainforest is so famous for.

Intentionally destroying the world’s largest terrestrial carbon dioxide sink, which plays a significant role in mitigating global warming, seems like a truly terrible idea. A tiny number of irresponsible and ignorant people may grow rich from it, but in the end we will all lose. If we continue despoiling the natural world and taking from it whatever we want, there will be far more penalties than benefits – not only for humans, but the entire planet.

Pingback: What Animal Is It? - The Nature Nook What Animal Is It?